Forests: cause and solution to the climate crisis

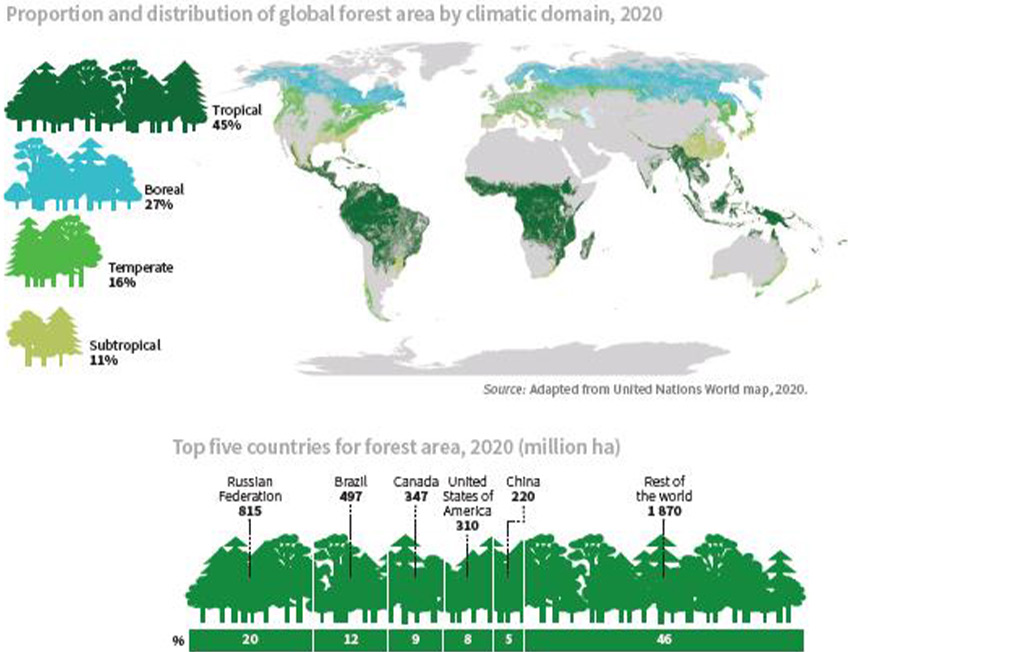

Forests are essential to the climate on Earth. They cover about 31% or roughly 4 billion hectares of the Earth’s land surface. As forests grow, their trees take in carbon from the air and store it as wood, plant matter, litter and soil. If not for forests, much of this carbon would remain in the atmosphere in the form of carbon dioxide, the most important greenhouse gas driving climate change.

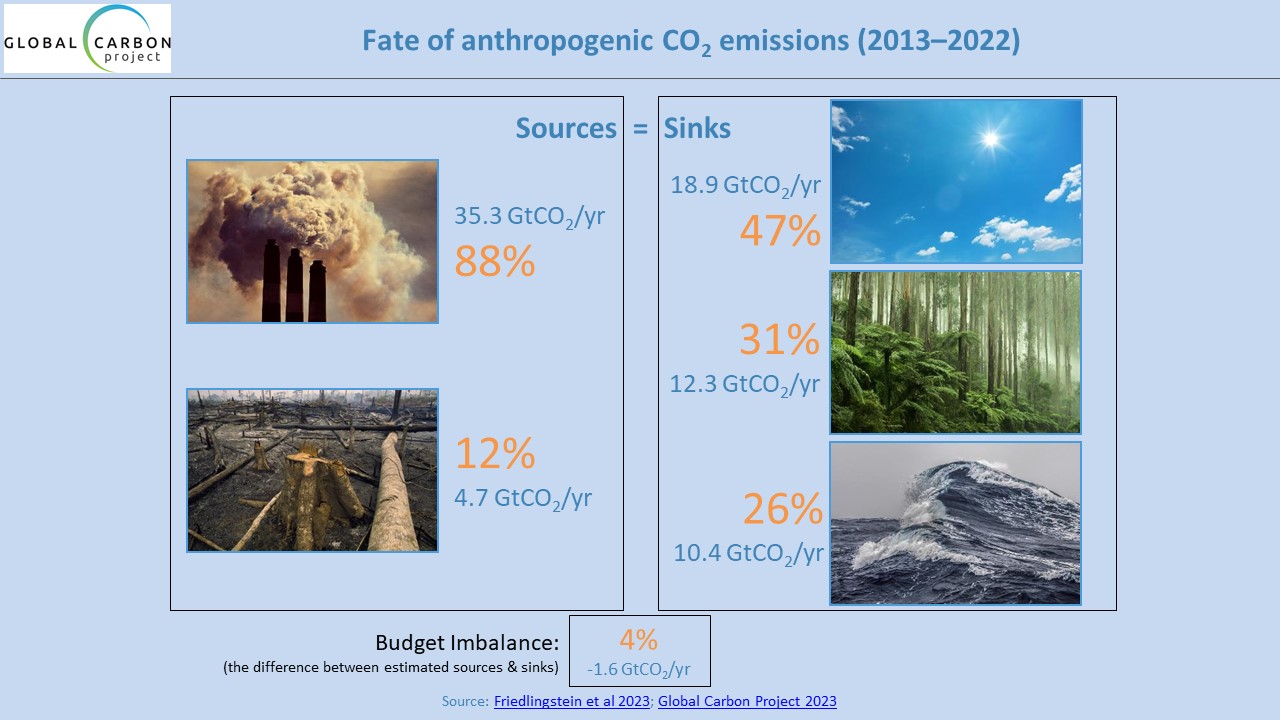

The “carbon sink function” of forests is slowing climate change by reducing the rate at which CO2, mainly from fossil fuel burning, builds up in the atmosphere. Healthy and well managed forests also provide a host of services. In fact forests, together with oceans, absorb more than half of anthropogenic fossil emissions. In 2023, according to the projection of the Global Carbon Budget emissions reached 36.8 billion tonnes of carbon dioxide (GtCO2), with rises expected in all fuel types (coal,oil, natural gas). This brings fossil CO2 emissions to a record high, and 1.4% above the 2019 pre-COVID-19 levels.

Source: FAO Forest Resource Assessment 2020

We as mankind owe a huge debt to forests and oceans that every year absorb half of our emissions and reduce global efforts to tackle climate change.

Forests regulate ecosystems, protect and host biodiversity, play an integral part of the carbon cycle, support livelihoods and can help drive sustainable growth. To maximise the climate benefits of forests, we must keep more forest landscapes intact, manage them more sustainably, and restore more of those landscapes which we have lost.

- Halting the loss and degradation of natural systems and promoting their restoration have the potential to contribute over one-third of the total climate change mitigation scientists say is required by 2030.

- Restoring 350 million hectares of degraded land in line with the Bonn Challenge could sequester up to 1.7 gigatonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent annually.

Forests can be managed in two ways to face the climate crisis: letting them grow or avoiding deforestation and forest degradation

What is the issue with forests?

The sink role of forests and oceans is now weakened and affected by rising temperatures and their ability to capture and store atmospheric carbon dioxide has been reduced.

Since 1990, the world has lost 178 million hectares, about 10% of total forests due to deforestation. Although the rate of deforestation has decreased since 1990, from 16 million to 10 million of hectares per year in 2021, significant forest losses still occur in Cambodia, Indonesia, Brazil and the Democratic Republic of Congo and many other countries. Deforestation of natural forests, complex ecosystems which have evolved over thousands of years, are only in part compensated by afforestation, simplified ecosystems, often a monoculture with few species of trees.

Primary forests or intact forest landscapes composed of native species without a visible sign of human intervention, cover 1.1 billion ha mainly concentrated in the tropics.

The loss of forest cover is responsible for at least 12% of global greenhouse gas emissions, but due to uncertainty in the estimates, this figure can reach up to 17%.

Emissions from deforestation, the main driver of global Land Use Change emissions, remained high at 6.7 GtCO2 per year over the 2012-2021 period.

The Amazon basin is drying up

Some forests, like the Amazon basin, are losing their ability to recover from disturbances like droughts, forest fires, fragmentation and land-use changes, adding to concern that the rainforest is approaching a tipping point. A tipping point is an irreversible state where some areas of the Amazon are drying up and becoming less resilient to disturbances, ending in being a net source of emissions.

The Amazon rainforest is home to a unique host of biodiversity, strongly influences rainfall all over South America by its enormous evapotranspiration, and stores huge amounts of carbon that could be released as greenhouse gas in the case of even partial dieback, in turn contributing to further global warming.

The new evidence comes from research conducted by the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research and the Global Systems Institute of the University of Exeter, derived from advanced statistical analysis of satellite data, of changes in vegetation biomass and productivity.

If this data provides a global picture and outlook on forests worldwide, each country facing forest losses and forest degradation has very different socio economic contexts, pressures and drivers behind deforestation.

I have visited several countries with significant loss of forest cover and forest degradation, from boreal forests in Canada, to tropical forests in Kenya, Cambodia, Myanmar and Vietnam.from my experience it is paramount that REDD+ policies are mandatory in the implementation of Nationally Determined Contribution or national climate plans submitted by countries that joined the Paris agreement. However this is not sufficient per se and it is necessary to pursue multilateral and bilateral agreements between countries whose actions are key in agricultural and forest supply chains that cause deforestation. Each supply chain has specific challenges and problems.

In Ghana, a country that since 1990 has lost nearly 90% of the forest cover, the main driver is the expansion of cocoa fields. In Myanmar deforestation is driven by the high demand for teak timber. Such is the global demand for the very valuable Myanmar teak, together with land conflicts in the Kachin State, that forests have decreased dramatically in the last decades. Western sanctions applied to teak exports did very little to stop the loss of teak natural forests, which are mostly located in Myanmar.

In Indonesia and Malaysia forest cover has dramatically decreased, caused by palm oil demand. Not only tropical but also boreal forests are threatened: in 2021 in North Eastern Russia at least 1,5 M hectares of forest has been lost due to forest fires.

In the European Union (EU), the awareness of deforestation is high and there are regulations and initiatives, like the Amsterdam Declaration Partnership, to tackle deforestation and sustainably manage forests. However even within the EU there are countries like Finland where deforestation, albeit legal, continues and Romania where illegal deforestation is a rampant problem.

These trends show how complex but nonetheless immediate action is required to reach the net deforestation target, stated in 2021 by the Glasgow Leader’s Declaration on Forests and Land Use. This declaration by 141 countries pledged to halve deforestation and reverse forest loss by 2030. Meeting this ambitious target involves a constant and long term decline of deforestation, that at the moment is not happening in key tropical countries’ hot spots of deforestation.

Now is the time to act to reduce the main drivers of deforestation and forest degradation: habitat fragmentation, climate change, increasing demand of agricultural commodities linked to deforestation, ecosystem degradation, exclusion of indigenous communities from their lands.