Time for change: delivering deforestation free supply chains

In the last five years 10 million hectares have been lost, roughly the area of Bulgaria every year. The loss of primary forests, particularly in tropical areas, continues at an alarming rate, with a huge long term impact on the Earth’s climate, biodiversity and people who live in the forests.

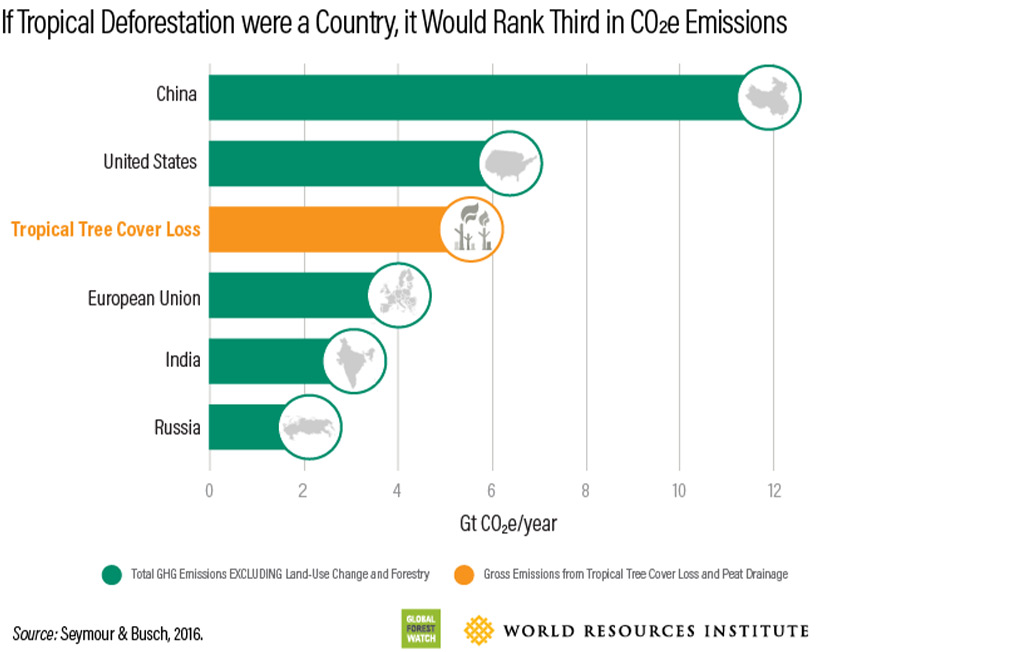

If deforestation was compared to a country in terms of emissions, it would be the third one in the world after the United States and China. Since 1960 around half of tropical forests have been lost, with strong evidence that demand for agricultural commodities and agricultural expansion are the main drivers

A recent study published in Science has confirmed that agricultural expansion is the dominant cause of tropical deforestation. Pasture expansion is the most dominant driver by far, accounting for around half of the deforestation, resulting in agricultural production across the tropics. Palm oil and soy cultivation together account for at least a fifth, and six other crops – rubber, cocoa, coffee, rice, maize and cassava likely account for most of the remainder, with large regional variations and degree of uncertainties.

Supply chain and demand side measures must be designed in a way that addresses the underlying and indirect ways in which agriculture is linked to deforestation. These side measures need to drive improvements in sustainable rural development, otherwise deforestation rates will remain stubbornly high in many places.

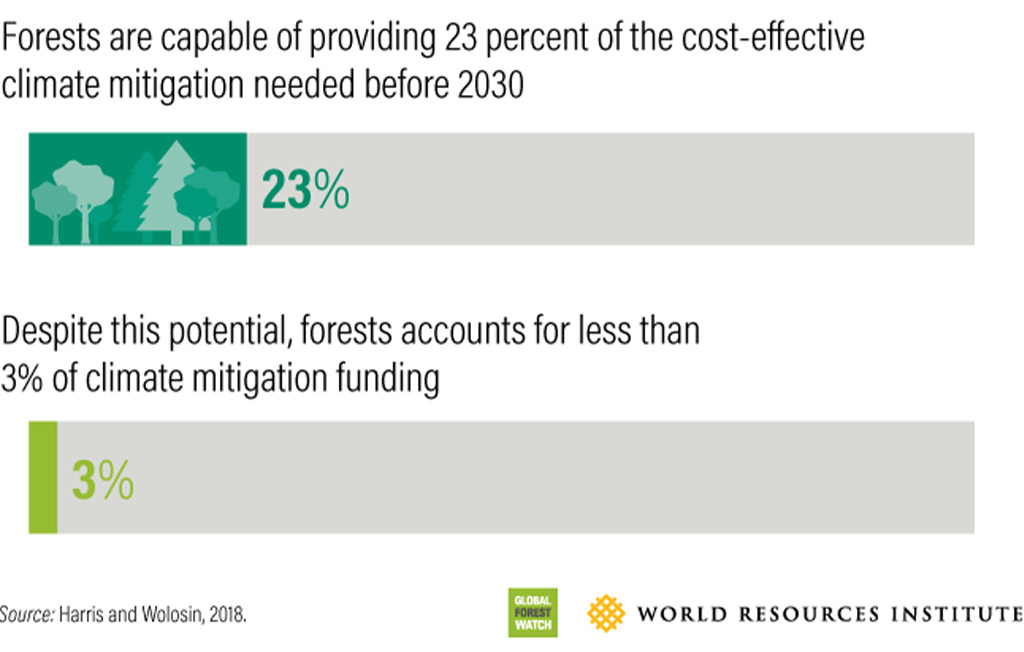

More comforting news comes from recent studies indicating that nature and land use solutions can contribute up to 37% or 11.3 Gt CO2 of the climate mitigation required by 2030 and limit warming to within a 2C increase. Of this important contribution, almost two thirds can be achieved through forest conservation and restoration and improved management of tropical forests, mangrove and peatlands. To implement them, systemic action is needed to redirect investment and funds and reduce deforestation.

Local impacts, global drivers

Globally, the main drivers of deforestation and forest degradation are linked to a handful of agricultural commodities that cause land use change such as palm oil and soy, coffee, cocoa, meat and maize followed by other products like rubber, leather, timber, as well as infrastructures like roads, dams, oilpipes and not least mining.

In tropical forests, at the heart of the problem lies agricultural expansion driven by the demand of agricultural commodities, but also more complex causes like market pressure, food preferences, lifestyles, inefficiency in some agricultural practices and food waste.

In European temperate, North-American and Russian boreal forests, the main cause of deforestation and forest degradation is timber demand ( 83%) followed by forest fires (12.7%) and urban sprawl (2.2%).

Why is Europe part of the problem?

EU consumption accounts for about 10% of global deforestation. This might not sound a lot, nonetheless Europe has a leading position on environmental and climate policies worldwide and is able to influence global trade. Data and studies show that Europe is one of the biggest importer of commodities linked to deforestation or Forest Risk Commodities ( FRCs) as shown in the pie chart.

For some commodities like cocoa, the EU is the world’s largest importer of cocoa beans, responsible for over 60 per cent of global imports. Although only some cocoa imports are linked to deforestation,r the main producing countries, Ivory Coast and Ghana, have faced high deforestation rates in the last 20 years.

The impact of EU consumption on deforestation is so relevant that in 2021 the EU Commission, at the request of the EU Parliament, presented a Proposal for a Regulation on deforestation free products.

The deforestation rate is so alarming that climate targets will not be met without a serious and fast crackdown on deforestation..

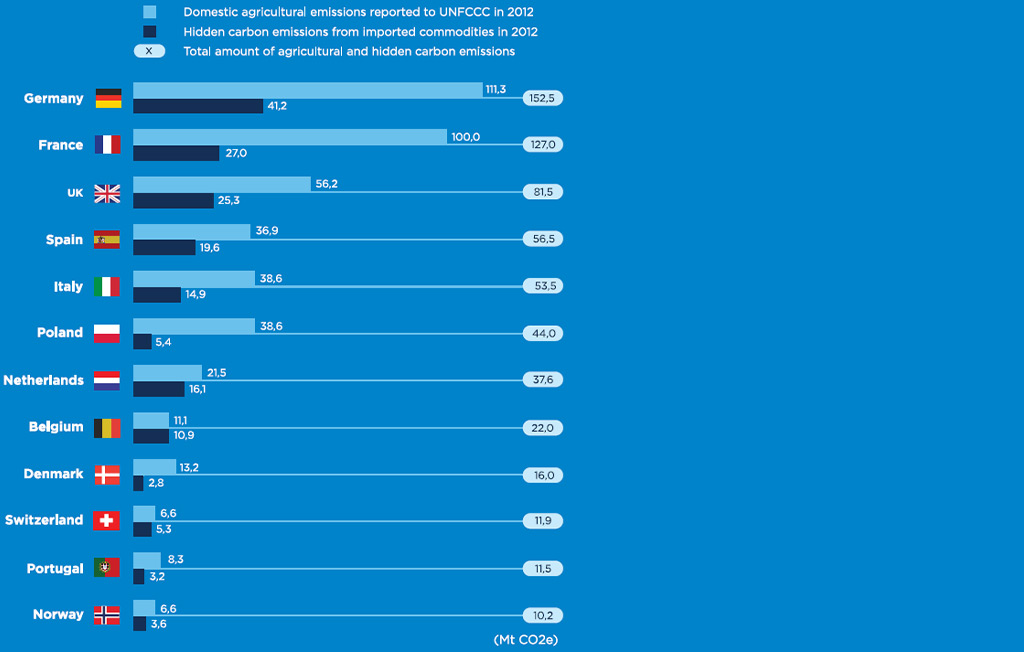

The responsibility of EU countries depends on the mix of FRC imports and their consumption.Nine EU countries are more exposed to deforestation and overall are responsible for 70% of FRCs.

A critical issue in the identification of responsibilities in the consumption of FRCs is that importing countries do not account related emissions to deforestation, which are instead attributed to producing countries in their national GHG inventories.

Multilateral actions, targets still to be met

Without a binding international agreement, European and national Regulations to track the impacts of FRCs along the supply chain, the private sector, NGOs, research institutions and governments are working to improve not only the monitoring of the supply chains, but also to reduce the risks. To this end, nine European countries have set up the Amsterdam Declaration Partnership, to work with key supply stakeholders and encourage them to reduce and minimize the impact.

Monitoring deforestation and forest degradation has remarkably improved recently, with satellite data available on Copernicus and Nasa platforms. The platform Global Forest Watch relies primarily on freely available medium-resolution imagery (10-30 meter pixels) from NASA’s Landsat or the European Space Agency’s Sentinel and it allows tracking of deforestation in exposed countries.

New and innovative open tools have been developed to track deforestation. Among them, Trase Earth is a revolutionary data – driven transparency initiative, developed by the Stockholm Environment Institute and The Global Canopy, that is able to monitor the trade and financing of commodities driving deforestation worldwide. It maps supply chains combining self-disclosed data from companies with customs, shipping, tax and logistics linking consumer countries to traders and places of production. It shows how commodity exports are linked to environmental and social harms in the places where they are produced. Trase’s freely available tools enable companies, financial institutions, governments and citizens to take practical steps to address deforestation. It already covers over half the global trade in forest-risk commodities and continues to expand coverage to new commodities. It maps supply chains and financing of key commodities from entire countries and regions, such as Brazilian soy or Indonesian palm oil exports, providing a wall-to-wall map of the central stages of a supply chain.

At the forefront of commodity certification and sustainable production, long running schemes such as FairTrade and RainForest Alliance, have joined forces with the aim of better visualizing and assessing deforestation risks in locations where there are certified producer organizations. For some highly traded and risky commodities such as palm oil and soya, specific certification standards have been developed, permanent round tables with NGOs, market players and government set ups.

The private sector and multinational companies have often developed their own standards to track and improve the impacts of their commodities in the value chains .In the last years there has been an increase of hybrid forms of sustainable governance within big industries and multinationals. Nespresso has launched the AAA Sustainable Quality Program to improve sustainability standards in coffee plantations.

In parallel, alliances and coalitions between multiple players in the supply chain including producers, buyers, government intermediaries, civil societies and governments to face issues such as minimum wage, deforestation and minimum price for producers. Global Coffee Platform, Cocoa&Forests Initiative and Soft Commodities Forum are examples of coalitions set up by global food giants and Consumers Goods Forum.

Several independent supply platforms, developed by high profile non profit organisations, are now available for the private sector to track supply chains at high risk of land use change. One of the best and most accurate is Global Forest Watch Pro, which provides maps and tools to private entities to identify land risks linked to the supply of some commodities.

Globally more than 150 private companies are committed to reach a zero deforestation target in their supply chains but targets are not sufficiently ambitious to generate a significant impact

If tracking impacts is improving at the same rate l as corporate initiatives,then why does deforestation continue at such an alarming rate? First of all, not all deforestation is driven by high risk commodities. In the African continent practices such as slash and burn and shifting agriculture to increase agricultural land for self consumption and local food demand, are widespread.

At the forefront of global consumption patterns, some companies are committed to reducing deforestation in their supply chains, others accept “zero net deforestation”, offset by reforestation plans. Also for the majority of companies committed to reducing deforestation, their pledges include a 2020 cut off date, not updated to 2030.

According to Forest 500, an ambitious and important project, supported by the Global Canopy, to monitor and assess pledges of companies and financial institutions exposed to deforestation in their activities, key findings in the evaluation of their results suggest the following outcomes:

- three quarters of 350 monitored companies don’t have pledges on all activities and supply chains; 117 of the 350 companies don’t have any commitment

- several companies committed to reducing deforestation don’t provide evidence on how they will implement targets, in particular for soya, meat and leather supply chains

- companies assessed by Forest 500 don’t have an adopted ethical Code of Conduct to show respect of human rights toward local people and ignore the human costs of deforestation

Forest500 initiative and transparency platform has increased not only transparency in companies commitments but also those of financial institutions, whose impacts are more opaque and are less accountable through financial ramifications.

Global investments that support deforestation still account for more than $ 5,5 trillion, while nature based solutions receive only 2,5% of climate finance.

The EU Regulation on deforestation, adopted on May 2023, could represent a game changer. A key requirement of the Regulation is a binding due diligence by operatorsand importers of products linked to deforestation, to prove that imported commodities are risk free. Another innovative element is a benchmark evaluation of exporting countries, based on their deforestation rates since implementation.

The Regulation could be improved, as proposed by a Green Peace Report and from the NGO Fern in an opinion paper. Nonetheless the adoption represents a radical change toward deforestation, where European importers in the food and agriculture sectors are called to address.

Link: Global forest monitoring