How to discuss the climate crisis?

Climate negotiations are complex processes due to the interdisciplinary issues at stake and the multilateralism of the parties. Organizing climate discussion is a challenging and rewarding experience given the wide range of knowledge and experience required. It can also be rather frustrating due to the slow progress and the perception of the gap between the speed of climate change and the lengthy implementation of action.

Historically, international climate negotiations like the UN Conference of the Parties (COP) are difficult processes because countries not only seek to protect their interest, primarily economic, but they are also exposed differently to climate risks. Plenary multilateral sessions, where delegates from the 195 signatory countries of the Paris Agreement meet, are events where progress is very slow and often focused on details that matter for some countries, while are irrelevant for others.

I joined two UN climate conferences: in Bonn (Germany) in 2017 and in Katowice (Poland) as a delegate of the European Commission. I remember a sense of frustration due to the difficulties of finding an agreement and the focus on details that seemed trivial given the scale of the problem and the urgency to implement climate actions. The agreement during the last hours of the extended night time for negotiation. On the other hand , the UN multilateral climate negotiation is a unique process in the world, that requires all countries to agree on the final text. It is a flawed but also necessary process.

Common target, different priorities

One of the elements of tension depends on the fact that some countries are more affected than others by the climate crisis. Among the most exposed countries and people, there are the indigenous groups from Arctic regions, Pacific islands, Sahel countries. At one of the last Conferences of the Parties

(COPs), Mia Mottley, Barbados’ Prime Minister, not exactly a political giant, emerged as a global climate leader calling on rich nations to do more to help the developing world fight climate change. She addressed rich nations with a rip-roaring speech telling the leaders of the world’s largest economies to “try harder” to avert catastrophic climate change. A 2C˚ overheated world “is a death sentence,” she said. New leaders emerge from these negotiations, an element that gives weight and power to small countries, often excluded from other high profile negotiations.

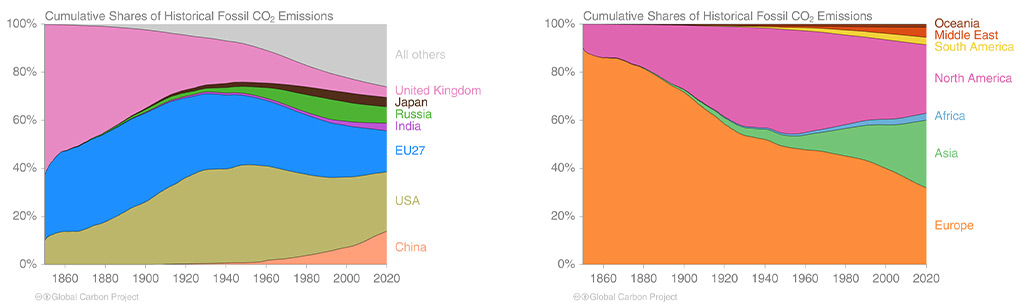

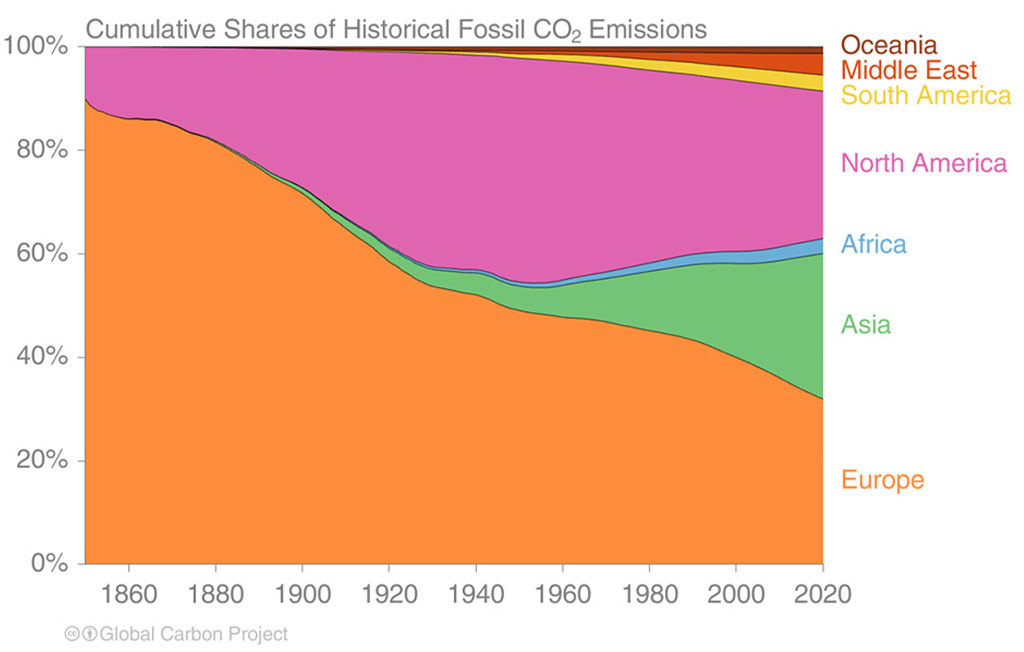

Source: Global Carbon Project 2021

Common but differentiated responsibilities

Since its inception, a question has permeated climate change governance. How do we differentiate between countries’ responsibilities while most effectively addressing the climate crisis?

All states have a shared obligation to address climate change, but they are not equally responsible.

Western public opinion and politics blame China and India for not doing enough to address climate change.

Several developing countries, like China – now the largest GHG emitter in the world – are deemed responsible for the emissions record. Without their commitment to disinvest from fossil fuels, especially from coal, the global target to keep the temperature rise within 1,5 C° is getting further away.

Looking historically at the climate crisis from the viewpoint of the most impacted countries and fast developing countries, the shared opinion is that the most industrialized countries have benefitted from decades of fossil fuels growth. This economic growth of the most developed nations, including the US and the EU, without an emissions cap for decades, has generated global warming. These issues are still stumbling blocks to a full implementation of the Paris agreement.

Money, money, money

Facing the climate crisis requires innovative technologies, infrastructures and knowledge that the least developed countries, often the most exposed to climate risks, often don’t have or represent out of reach costs.

The Paris Agreement had committed to mobilizing 100 billion ? $ per year to help developing countries in the energy transition. So far the $100 billion pledge falls far short of poor nations’ actual needs, but has become symbolic of wealthy countries’ failure to deliver promised climate funds. This has fuelled mistrust in wider climate negotiations between countries attempting to boost CO2-cutting measures. The concept of climate finance is also interpreted differently: as development aid for some countries, as specific climate adaptation support for others. Details matter when it comes to financial commitments.

Beyond the difficulties that UN climate negotiations face, at national and local level the climate debate is often influenced by economic interests, lobby groups and the short term visions of politics.

At whatever level the debate takes place, it is paramount to prepare for the discussion to face complexity, multiple interests and ultimately also climate change denial.

How to discuss the climate crisis in a constructive way

Source: photo adapted from Viktor Talashuk and Behavioral Scientist

There are sound, proven and effective methodologies to reach good outcomes when debating complex and polarized subjects, where parties represent different interests if not conflicting groups.

Oxford Union Method

The Oxford Union method is a widely used debate style adopted in complex and polarized debates. It has been used in political debates on the IRA in Ireland, on WaterGate and on Israeli- Palestinian negotiations.

When the Oxford Method is applied to climate and environmental debates, the model is typically based on the definition of a proposition. Are GM crops safe or dangerous? Can solar energy contribute to decarbonising the energy sectors in the short term? Is nuclear power a clean source of energy?

The debated proposition is introduced by a speaker, who keeps a neutral position and moderates the discussion. The debating parties present their opinions, supporting factsheets and formulating questions. Time is allocated in a fair and balanced way. The audience finally expresses the final conclusion with the support of the speaker.

The method helps to develop critical thinking, tolerance of different opinions, a sound background, peer reviewed research information and capacity to change and support opinions in a logical structured and coherent way.

Role Playing Method

The underlying idea of the Role Playing Method or RPS (Role Play Simulations) is to simulate the parties at stake in a debate. The RPS creates a realistic albeit simplified situation where parties “play” a real player and are committed to a dialogue. They experiment with a portfolio of solutions before reaching an agreement. Players learn how to respect different opinions and how to deal with multiple conflicting opinions and often play the part of an opponent. They can explore complex and controversial issues without direct political, financial, economic or personal consequences.

I joined several debates organized according to the RPS method on subjects where a multitude of players are involved. How to tackle deforestation in the world? How to address the climate crisis?

One of the most complex and challenging elements was understanding parties whose positions and often values were conflicting. This exercise allows us to partially give in on our contra positions, often real walls to a negotiation and stumbling blocks to constructive agreements.

There are several variants to the RPS, including the role inversion method. The inversion method invites players to take the viewpoint and opinion of participants with a conflicting or different opinion. This approach leads to more propensity towards negotiation, attention to the different positions of parties and facilitates the understanding of others

Whatever is the adopted methodology, before starting a debate or negotiation on climate issues it is appropriate to define how to carry them out, allocation of time, goals and realistic outcomes.